During the month of June, LGBTQ+ Pride Month celebrations take place in the United States and worldwide, commemorating the June 1969 Stonewall Uprising in Manhattan, New York, a turning point in gay rights and liberation movements. As the U.S. Proclamation on LGBTQ+ Pride Month 2021 states:

Pride is a time to recall the trials the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ+) community has endured and to rejoice in the triumphs of trailblazing individuals who have bravely fought — and continue to fight — for full equality. Pride is both a jubilant communal celebration of visibility and a personal celebration of self-worth and dignity.

“A Proclamation on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Pride Month, 2021,” The White House, 1 June 2021

It can be a tricky thing to recognize the dangerous and often-deadly discrimination that the LGBTQ+ community has endured — and continue to endure — at the same time that you are celebrating the wide-ranging contributions and impact of the LGBTQ+ community. This means holding space for two extremes together at the same time, and hopefully, this is a time of deep reflection and grace for us all, including allies. I feel that the movie Prick Up Your Ears (1987), which is based on the real-life events of British playwright Joe Orton (born John Orton, 1933-1967), exemplifies this dynamic quite well.

Directed by Stephen Frears (My Beautiful Laundrette, Dangerous Liaisons, The Queen), Prick Up Your Ears stars Gary Oldman as Orton; Alfred Molina as Orton’s mentor, collaborator, and lover Kenneth Halliwell; and Vanessa Redgrave as Orton’s literary agent, Peggy Ramsay. The movie, written by Alan Bennett, was adapted from the 1978 biography of the same title by John Lahr, and Wallace Shawn plays Lahr in this film adaptation.

Joe Orton’s plays (most notably, Entertaining Mr. Sloane and Loot) and writing style continue to be highly influential (e.g. the term “Ortonesque” is used to describe the witty and dark comedic style he specialized in), even though his public career lasted only a few short years, from 1964 to 1967. Orton’s and Halliwell’s 15-year relationship came to a violent end in August 1967, when Halliwell murdered Orton and then killed himself. It could be easy to dismiss the film as focusing too much on the sensational aspects of this true tale. The film trailer, embedded above, focuses primarily on the murder/suicide, and the film itself begins with Halliwell covered in blood after murdering Orton and ends with Orton’s funeral. But in-between, we follow along with the flashbacks and flash-forwards as Lahr researches Orton and reads his diaries and pieces together Orton’s and Halliwell’s life together. (You really cannot separate the two men, in life or in death.) We viewers identify with Lahr in his research quest, as we want to know more about Orton’s art and about Halliwell’s motivations, and how and why their relationship and collaborations soured and turned deadly. It’s not a straightforward film, but Frears does an excellent job of highlighting recurring themes and lines that call back to earlier scenes or other characters.

A few years ago, The Guardian highlighted Lahr’s biography of Orton as a “book to give you hope.”

“John Lahr’s 1978 biography of the playwright Joe Orton may seem an unlikely choice for a book to give you hope. After all, Orton’s success was not only a long time coming (a decade of abject failure was crowned by a six-month spell in prison for defacing library books), but when it did finally arrive in 1964 (with the West End production of Entertaining Mr Sloane) it lasted only until 9 August 1967. It was brought to a bloody and premature end by his long-term lover, Kenneth Halliwell, who bludgeoned Orton to death with a hammer before taking his own life. Orton was only 34 years old. Yet, it is these early years of struggle and anonymity that make Orton’s life story such a fascinating and, yes, inspirational read.

… [T]he ending is desperately sad. But what remains is the work. And ultimately, Prick Up Your Ears is a celebration of Orton’s work and a brilliantly illuminating account of the writing life. And even when that life is cut horribly short, it still remains a testament to the enduring power of hope, and of triumph over adversity.”

W.B. Gooderham, “Books to Give You Hope: Prick Up Your Ears by John Lahr,” The Guardian, 22 Aug. 2016

For me, this review captures the juxtaposition of recognizing the sadness of Orton’s shortened life as well as celebrating the hope and creativity of his artistry. And this dichotomy is reflected in Frears’s cinematic adaptation.

The library scenes and why they matter

So where does the library come into it? Although the main library scene and scenes with the librarians last less than 5 minutes total, this scene in the movie — and in real life — changed the course of Orton’s and Halliwell’s lives. It seems appropriate then that the library scenes occurs almost exactly halfway through the movie.

Here’s the general background: Around 1959, while collaborating on novels and getting rejected from publishers, Orton and Halliwell started defacing covers of library books and typing naughty passages into them. In the movie, two librarians at the Islington public library finally set a trap for them and turned them into the police. In 1962, the two men were sentenced to 6 months in prison and were sent to different facilities. While in prison, Orton started writing his own work and flourished, while Halliwell became depressed and attempted suicide.

The library book scenes are foreshadowed a bit earlier in the film, when at 44 minutes, Halliwell and Orton are collaborating on a book. While Kenneth types on the typewriter, Joe is cutting up a library book.

Kenneth: That’s a library book. You should respect books.

Joe: I respect them more than you. You just take them for granted.

This short scene accomplishes a lot with a little. They are supposedly collaborating, but Joe seems a bit bored and stifled with his side of the collaboration. This foreshadows his breaking free and writing his own works later. Their dialog also reinforces their class differences, with working-class Joe calling out Kenneth and his upper-class upbringing and privilege. It also, as my writer husband pointed out, places the act of defacing the library books in the context of writing and as a creative act and form of expression. They are writing and creating in different ways in this scene, and again, it foreshadows how they will collaborate on the library books.

Next, at 45 1/2 minutes into the film, Halliwell and Orton are talking about that collaborative novel, titled Boy Hairdresser, to a publisher. When it’s clear that the publisher has no intention of publishing their work, Orton roams around the office and steals a book from the publisher’s shelves, The Art of Culture. Although it isn’t explicitly shown in the movie, Orton revealed in later interviews that he used to steal library books in order to deface them and then smuggle them back into the library to shock patrons who came across the altered works.

So all these short, seemingly throwaway scenes do provide clues; nothing is wasted in this movie.

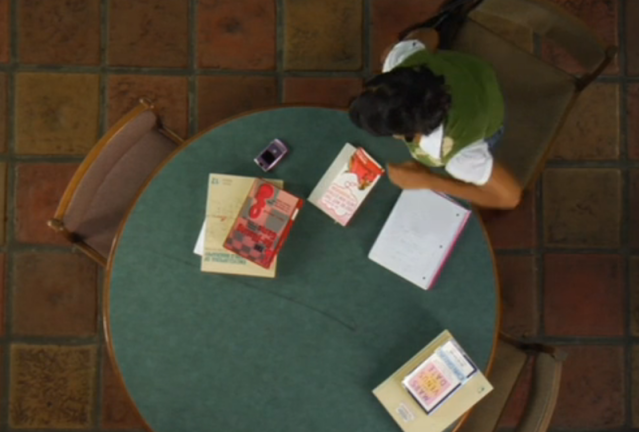

At almost 53 minutes into the film, Kenneth is working on the collage on the walls, while Joe is reading on the bed. Then, as Kenneth prepares lunch, Joe roams around their bedroom and places library books along the back of their desk.

Joe: I can’t see how we’re ever going to make our mark… defacing library books.

Next stop? The public library!

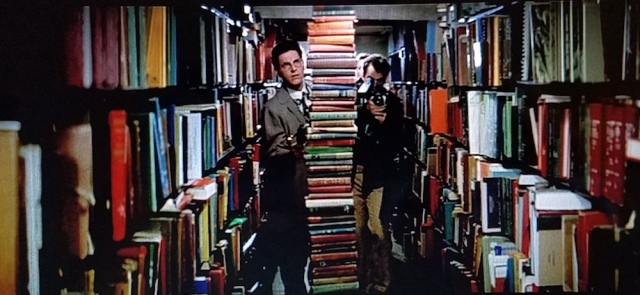

The two men check out books at the front library counter, and a woman librarian in grey suit stamps their books. We can also spy a younger White woman walk past behind the desk, and she appears to be filing cards. In the background, we can see a “Fiction” label along the back bookshelves, and the library seems filled with patrons. Halliwell and Orton leave the library, and the words on the exit door — “Way Out” in big letters printed on both sides of the glass door — feature prominently in this scene. That doesn’t feel like an accident. (In fact, the phrase “coming out” was in use during the mid-20th century to describe gay identity and sense of community, but the phrase was undergoing a change in usage during this time period, explained here.)

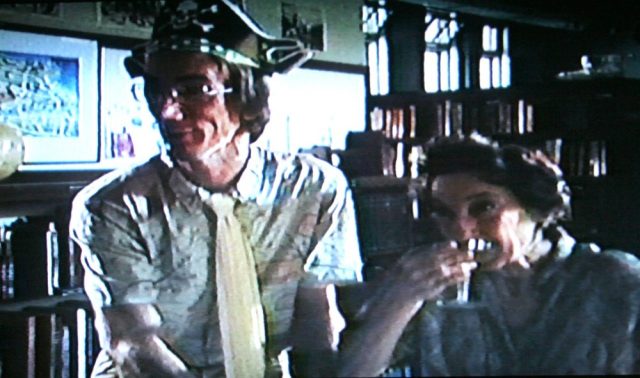

Two librarians — the middle-aged White woman who stamped their books, Miss Battersby (Selina Cadell), and a White middle-aged man, Mr. Cunliffe (Charles McKeown) — follow them out and watch them leave.

Their brief conversation reveals their discrimination and homophobia toward the pair and the gay community at large, and Mr. Cunliffe rattles off several homophobic slurs without batting an eye.

Mr. Cunliffe: You didn’t tell me one of them was a nancy.

Miss Battersby: I’m sorry, Mr. Cunliffe?

Mr. Cunliffe: The bald one, Miss Battersby. A homosexual. A shirt lifter.

Miss Battersby: In Islington?

Mr. Cunliffe: Haven’t you noticed? Large areas of the borough are being restored and painted Thames green. [He grabs their library card from Miss Battersby] Noel Road. This calls for a little detective work, Miss Battersby.

And their detective work involves props! Miss Battersby smokes a cigarette, and Mr. Cunliffe brandishes a magnifying glass.

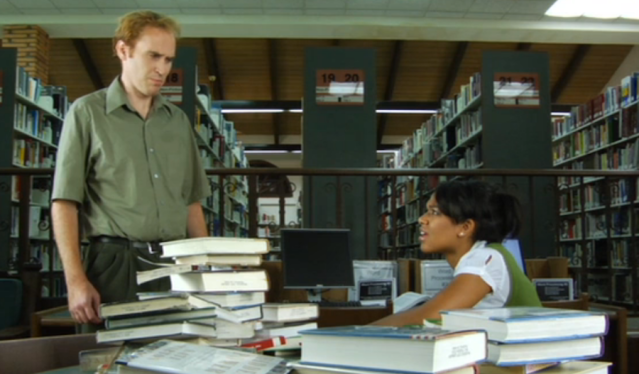

The librarians then set up a trap for Halliwell and Orton. Mr. Cunliffe finds an abandoned car on the road, writes down the license plate, and then dictates a letter to Miss Battersby. They appear to be in a back office in the library, as the walls are lined with bookshelves and filled with books and magazines, and the desk includes a pile of library stamps, and a rolling cart is visible beside the desk.

Mr. Cunliffe: Registration: K-Y-R-4-5-0. The above-mentioned vehicle appears to be derelict and abandoned in Noel Road, and I have been given to understand you are the owner thereof.

We then see Kenneth reading aloud the rest of the letter, and he then dictates a response to Joe, although their letter is a more collaborative process than the librarians’ letter.

Kenneth: “But before enforcing remedies, I give you the opportunity to remove the vehicle from the highway.” The little prick. [pauses] Unzip our trusty Remington, John. We will piss on this person from a great height. “Dear sir, thank you for your dreary little letter.

Joe: ‘Dismal’ is better.

Kenneth: Dismal, then. I should like to know who provided you with this mysterious information.

Joe: ‘Furnished’ is better than ‘provided.’ It’s more municipal in tone.

Cue more librarian detective work!

Mr. Cunliffe: You will note the typing, Miss Battersby, is the same. Our book jacket… their letter. Got you, my beauties.

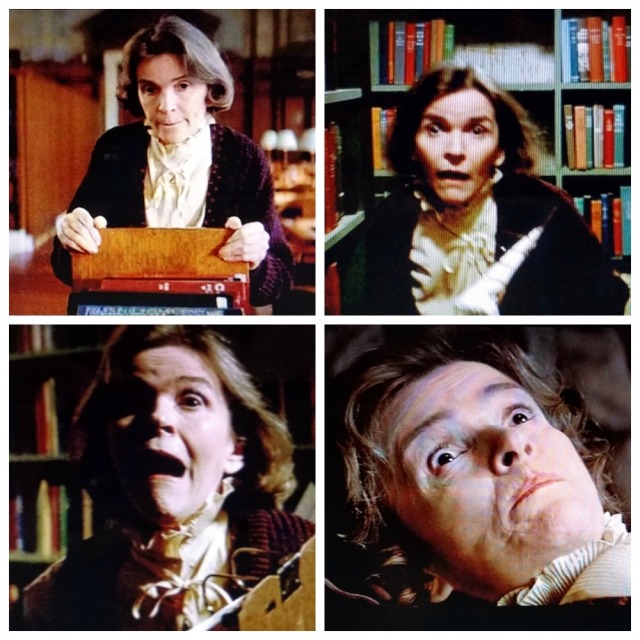

We then cut to the courtroom, where we see a magistrate being handed a mystery novel, Clouds of Witness by Dorothy L. Sayers. We see a stack of books on the table, which are recognizable as some of the ones we saw earlier on Joe’s desk. This scene is devastatingly efficient, as the camera pans over the courtroom, where we spy the librarians, who have come to see the results of their detective work!

Magistrate: This is the novel Clouds of Witness by the noted authoress Dorothy L. Sayers. Could you read what the accused have written on the flap of the jacket?

Policeman: “… This is one of the most enthralling stories ever written by Miss Sayers. Read it behind closed doors and have a good shit while you’re reading it.”

Magistrate: The probation officer has suggested that you are both frustrated authors. Well, if you’re so clever at making fun of what more talented people have written, you should have a shot at writing books yourselves. You won’t find that such a pushover. Sheer malice and destruction, the pair of you. I sentence you both to six months.

Joe [to Kenneth]: Fucking A.

Kenneth [to Joe]: It was your idea.

The librarians vs. the lovers

As I mentioned before, this entire scene in the library and with the librarians lasts less than 5 minutes, but it is crucial to the rest of the narrative. I also found it interesting to note how many times the director chose to mirror the pair of librarians with the pair of lovers, Orton and Halliwell.

Here is a compare-and-contrast of how Orton and Halliwell exit the library and the librarians re-enter the library. The librarians serve as gatekeepers — literally as well as visually — in this scene.

Here we can compare-and-contrast the profiles of the librarians as they watch in judgment as Orton and Halliwell leave the library, and the profiles of Joe and Kenneth as they receive the magistrate’s prison judgment.

The librarians sit in court in front of a policeman, while Orton and Halliwell sit in court in front of a member of the public. Again, no detail is wasted in this film. The librarians side with order (more visual gatekeeping), while the creative lovers side with the public.

And below we can compare the mirroring of dictating the library letter and its response. Both of the sets are filled with books, but one is a public library while the other is a private library. Also, notice how the librarians are always dressed in the same clothing, the same buttoned-up grey suits? Kenneth and Joe are also dressed in neutrals, grey and tan, but are dressed much more casually and less buttoned-down.

The library scene ends at 58 minutes into the film, and we hear Vanessa Redgrave’s voiceover as she efficiently sums up the effect of their prison sentence: “Prison worked wonders for Joe.”

Librarian roles

As I’ve mentioned, the two main librarians we see — Mr. Cunliffe and Miss Battersby — are visually seen as gatekeepers throughout their scenes. Their grey suits come off as much of a uniform as the uniforms that the police officers wear. The librarians even attend court to witness the prison sentencing! Above and beyond their librarian duties, surely. 😦 Needless to say, these reel librarians are NOT role models; rather, they demonstrate the destructive effects of homophobia and anti-LGBTQ+ actions.

In that way, Miss Battersby serves the role of an Information Provider, as she is providing information to the audience and reflecting society’s limited views and judgment of the LGBTQ+ community. (See also my post about the law librarian failure in Philadelphia). The third librarian, the younger White woman, also serves as an Information Provider, but only in the sense of establishing the library setting.

I have categorized the role of Mr. Cunliffe, who appears to be the senior librarian in their scenes, as an Anti-Social Librarian. He wears conservative clothing, hoards knowledge, dislikes the public (particularly the LGBTQ+ members of the public), and exhibits elitism in his view of the library and society in general. He goes beyond his librarian duties and engages in detective work — outside the library and off hours, I’m sure — in order to personally trap library patrons. He also relishes in his handiwork (“Got you, my beauties!“). Honestly, it comes off as the librarian’s personal vendetta.

And these two reel librarians made my Hall of Shame list! On that page, I wrote that:

This Class III film made me sit up and yell at the screen! It includes the completely unethical behavior of two librarians, who set a trap — using information from circulation records, no less! — to turn two frustrated writers into the police. Yes, the writers had typed obscene passages onto book covers, but that does not justify a mean-spirited librarian’s actions.

Reel life vs. real life

As I mentioned above, the film shows the librarians — and particularly Mr. Cunliffe — as the ones who personally trap Orton and Halliwell. I’m sure the screenwriter did this to condense characters and tell the story more efficiently — and of course, isn’t it shocking what an overzealous librarian would do?! Most unexpected. And it is unexpected, because the real-life librarians did not actually go as far as their onscreen counterparts did. But not for lack of trying!

The Joe Orton Online site states that Orton and Halliwell “had been suspected for some time and extra [library] staff had been drafted to catch the culprits, but with no success. They were eventually caught by the careful detective work of Sydney Porrett, a senior clerk with Islington Council. A letter was sent to Halliwell asking him to remove an illegally parked car. Their typed reply matched typeface irregularities in the defaced books and the men were caught.” And an article in The Guardian reveals more details, that “When the library authorities cottoned on to what was happening, they brought in undercover staff from other libraries to try to catch whomever was doing it, and when that failed, Porrett had the idea of writing to his number one suspects, Halliwell and Orton.”

The Movie Locations site reveals that the library scenes were not filmed in the Islington public library. Instead, the library scenes were filmed at Chelsea Library in Chelsea Old Town Hall, located about 6 miles southwest of Islington Central Library.

It does appear the the library books highlighted in the film were among the ones that Orton and Halliwell defaced in real life. The British Library site even highlights “The Joe Orton Collection” of book covers on their site, stating that, “Since 2003, the book covers have been preserved by the Islington Local History Centre where they form the Joe Orton Collection. After the trial, the surviving covers were kept within Islington Public Library Service by the special collections librarian. Today, this totals 41 examples. An additional 31 doctored books are believed to be lost, stolen or destroyed.“

You can also view a more extensive gallery of the book covers on the Joe Orton Online site. And in 2011, the Islington Local History Centre displayed their collection of book covers because of “international interest” and that the book covers “shined a light on two fascinating lives and characters” (Brown).

Why library books?

The movie doesn’t really delve deep into the reasons Orton and Halliwell defaced the library books — beyond the line that Joe says about “mak[ing] our mark” — but Orton did address this in an April 1967 television interview with Eamon Andrews:

Orton does not mention Halliwell at all during this interview and states that his motive was “just a joke.” But then he reveals a little more about his personal feelings about the library and its collections:

Orton: Also, I didn’t like libraries anyway. I mean, I thought they spent far too much public money on rubbish. I mean, I didn’t like the books. I don’t think people need books on etiquette anyway.

Andrews: So this was a kind of protest of the kinds of books in the library?

Orton: Oh, yes, it really was.

Andrews: Do you have any regrets now for having done this?

Orton: No regrets at all. No, I had a marvelous time in prison. It just meant that instead of annoying a few old ladies, you see, that opened the book, I now annoy hundreds of old ladies by writing plays.

The Joe Orton Online site muses that “these acts of guerrilla artwork were an early indication of Orton’s desire to shock and provoke. His targets were the genteel middle classes, authority and defenders of ‘morality’, against whom much of Orton’s later written work would rail against.”

In a 30th anniversary retrospective interview about the film, Alfred Molina (who portrayed Halliwell) reflected that, “Living in that small room, living in a sense completely isolated from the world, writing and defacing those books, and decorating their home, it was probably like a little cocoon where they felt safe. With Joe’s success, the world broke into that room and that shattered everything.”

I also appreciated blogger and historian John Levin’s thoughts about how these book covers should be viewed today:

“It is worth considering these works without hindsight and in their own moment. Had Orton not been successful, what would have been made of these works? Would they have been less interesting, less intelligent, the work of a vandal rather than a critic?

I think not. Even if Orton hadn’t been successful – and such a way of framing it underplays the equal contribution of the unrecognized Halliwell – these collages would still embody a contempt for boredom, a queer ‘in your face’ aesthetic, and a provocation outside the art gallery, executed with quite some skill. And as at the time, they were a couple of unknown, pre-1967 gays, constrained by and pushing against the mores and the policing of the time, it is in that light they should be appreciated.”

John Levin, “Gorilla in the Roses: The Collages of Halliwell and Orton,” Anterotesis, 21 Feb. 2012

And on a final note, Orton also included cheeky references to libraries and librarians in his play Entertaining Mr. Sloane, which I highlighted in my analysis of the 1970 film adaptation of his play.

What are your thoughts on Prick Up Your Ears? Have you seen the 1987 movie, or read Lahr’s biography? Have you read any of Orton’s plays? Please leave a comment and share!

Sources used

- Brown, Mark. “Library books defaced by prankster playwright Joe Orton go on show.” The Guardian, 11 Oct. 2011.

- “Coming out” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

- Gooderham, W. B. “Books to Give You Hope: Prick Up Your Ears by John Lahr.” The Guardian, 22 Aug. 2016.

- “Joe Orton” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

- Joe Orton Online. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- “Kenneth Halliwell” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

- Lang, Brent. “‘Prick Up Your Ears’ at 30: Alfred Molina Reflects on Film,” Variety, 24 Aug. 2017.

- Levin, John. “Gorilla in the Roses: The Collages of Halliwell and Orton.” Anterotesis, 21 Feb. 2012.

- “LGBT History” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

- “Library Book Covers Defaced by Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell.” Discovering Literature: 20th Century Collection Items. British Library. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- Prick Up Your Ears. Dir. Stephen Frears. Perf. Gary Oldman, Alfred Molina, Vanessa Redgrave, Wallace Shawn. Samuel Goldwyn Co., 1987.

- “Prick Up Your Ears” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license.

- “Prick Up Your Ears | 1987.” Movie-Locations.com. Accessed 21 June 2021.

- “A Proclamation on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Pride Month, 2021.” The White House, 1 June 2021.

- Snoek-Brown, Jennifer. “Hall of Shame.” Reel Librarians, 7 Oct. 2011.