I recently rewatched the 1966 film version of Fahrenheit 451, directed by French New Wave director Francois Truffaut and starring Julie Christie in a dual role and Oscar Werner as Montag, the fireman who falls in love with books, the very thing he’s charged with burning.

*MAJOR SPOILER ALERTS THROUGHOUT*

Here is one of the original trailers for the film:

The origins of Fahrenheit 451:

One of the major themes of the book, and resulting film, is about authoritarian censorship, the kind that led to book-burning in World War II. The finished novel of Fahrenheit 451 was first published in 1953, so this was still fresh in people’s minds.

The origins of the book, however, actually go back to 1947-1948, right after the war ended, when Bradbury wrote a short story, “Bright Phoenix.” This story featured a librarian who confronted a book-burning “Chief Censor.” Bradbury turned that story, plus another story in 1951 called “The Pedestrian” set in a totalitarian future, into the novella called “The Fireman,” which was published in the February 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction. Bradbury relished retelling the story about how he wrote “The Fireman” (which essentially serves as the first draft of Fahrenheit 451) in 9 days on a typewriter he rented in the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library for ten cents per half hour. He then expanded that story into the novel we know today.

In a dystopian future — one again, like in The Handmaid’s Tale, is too eerily familiar to modern times — books are forbidden and burned when discovered. In this future, firemen are trained to burn books, rather than prevent fires. Neighbors are encouraged to spy on one another and report those they suspect have books. Information (or rather, propaganda) is spread through television, called “wall screens,” as well as through comics-like publications, as seen in the screenshot below.

The hidden library scene:

A turning point in the film comes almost exactly halfway through the film, when Montag is called to the house where he knows Clarisse lives. Clarisse is described as Montag’s “rebellious, book-collecting mistress” on the back of the DVD case, but her role in the film is much tamer than that description suggests. His supervisor, Captain Beatty (played by Cyril Cusack), discovers a “hidden library” in the attic and cannot hold back his glee at the prospect of burning all those books:

I knew it. Of course, all this — the existence of a secret library was known in high places, but there was no way of getting at it. Only once before have I seen so many books in one place. I was just an ordinary fireman at the time.

It’s all ours, Montag.

Once to each fireman, at least once in his career, he just itches to know what those books are all about. He just aches to know. Isn’t that so? Take my word for it, Montag, there’s nothing there. The books have nothing to say!

During this scene and monologue — only the captain is talking, Montag only reacts — Captain Beatty expounds on different types of books and genres, dismissing each in turn. At the end, he finally reveals the reasons behind this society’s book-burning:

We’ve all got to be alike. The only way to be happy is for everyone to be made equal. So, we must burn the books, Montag. All the books.

This scene reminded me of the forbidden magazines scene in The Handmaid’s Tale and the reasons the Commander gave for their totalitarian regime. The reasons in The Handmaid’s Tale were different, that they needed to “cleanse” all the dirt and filth and sex from the world. The reasons expressed in Fahrenheit 451 come off as a search for a mythical, Utopian, and elusive “pursuit of happiness.” A generic happiness, but happiness nonetheless.

Modern martyrs:

The captain’s assertion that “the books have nothing to say” is directly contradicted in the next scene, in which the older woman refuses to leave her books.

Fabian, another fireman, rushes in to say that the woman won’t leave. “She won’t leave her books, she says.”

Woman: I want to die as I’ve lived.

Captain Beatty: Oh, you must have read that in there. I’m not going to ask you again. Are you going?

Woman: These books were alive. They spoke to me.

And so the older woman lights the match herself, to die as she lived, with her beloved books.

Truffaut also lingers several minutes over the burning of the books, with several close-ups.

In the final act of the film, Montag and his firemen troop are called to his own house. He is forced to burn his own hidden collection of books.

He is chastised and criticized by his captain:

What did Montag hope to get out of all this? Happiness? What a poor idiot you must have been.

His captain tries to grab the last book from Montag’s hand — we find out later this is a collection of Edgar Allan Poe’s stories, Tales of Mystery and Imagination — but Montag finally breaks, blasting Captain Beatty with the fire hose instead.

Now compare this photo, of his captain lying facedown in the pile of books, ablaze, with the previous screenshot of the older woman, standing upright, proud and defiant. Both are martyrs of their own kind, but the woman chose to go up in flames.

The book people:

Montag goes on the run then, hunted by the state, but he manages to escape to a hidden Utopia, deep in the forest, where others have escaped and banded together. These people are known as the “Book People,” as they have memorized a single work of literature and recite their tales for anyone who wishes to hear. The “book people” scenes were also filmed last.

Here’s how the leader of the camp describes how they came together, the 50 or so at their station. But he mentions there are more of the books:

In abandoned railway yards, wandering the roads. Tramps outwardly, but, inwardly, libraries.

It wasn’t planned. It just so happened that a man here and a man there loved some book. And rather than lose it, he learned it. And we came together. We’re a minority of undesirables crying out in the wilderness. But it won’t always be so. One day we shall be called on, one by one, to recite what we’ve learned. And then books will be printed again. And when the next age of darkness comes, those who come after us will do again as we have done.

And the book people also burn books themselves! But like the older woman in the house, they choose to do so, for their own specific reasons.

Yes, we burn the books. But we keep them up here [pointing to the brain] where nobody can find them.

The book people have literally “become” their chosen book and even introduce themselves as such:

“Are you interested in Plato’s Republic?”

“Well, I am Plato’s Republic. I’ll recite myself for you whenever you like.”“I am The Prince by Machiavelli. As you see, you can’t judge a book by its cover.”

“That man over there hasn’t much longer to live.”

“He’s The Weir or Germiston by Robert Louis Stevenson. The boy is his nephew. He’s now reciting himself, so the boy can become the book.”

The film clip below is a combination of the final two scenes from the film.

In a special “making of” featurette in the DVD’s special features, film historian and professor Annette Ensdorf gave her own interpretation of the film’s final scenes among the “book people,” stating that the people reciting their books at the end are just as self-absorbed as the narcissists we saw at the beginning of the film. Ensdorf sums up the finale and the “book people” as:

…instruments of the text — not really existing as a completely integrated social community but rather as individual icons.

But there’s the feeling of a certain muted triumph, namely that the book people will maintain a portion of civilization, that someday these books will still be alive, even if they are recounted rather than as written text.

Classification and connections:

Although the people literally become books in the end and could therefore be argued to be the only thing left resembling a librarian in a futuristic sense, I have to categorize this film in the Class V category, films with no identifiable librarians, although they might mention librarians or have scenes set in libraries. There are definitely library and censorship themes in the film, but no actual, identifiable librarians.

This contrasts with the “Books” in another sci-fi classic, Soylent Green. In Soylent Green, “Books” are former librarians and professors who become personal researchers in a dystopian future, a world in which books have ceased to be written and published. Books become rare commodities, precious treasures to be hoarded — but not due to fear of burning. Rather, books — and the people who take care of them, who then are referred to as “Books” themselves — are almost revered, and they have a unique power of their own.

In Soylent Green, the “Books” guard the past, but there is little hope for the future.

In Fahrenheit 451, however, the “Book People” guard, or consume, the past because they are the only hope for the future.

Books in Fahrenheit 451:

Here’s a list I compiled of all the books mentioned in the final scenes, in the order they are mentioned. The leader mentions there are around 50 or so around their camp, but says there are many others out there. A southern camp is also mentioned in the last scene.

These are some of the books we know that will live on:

- Plato’s Republic

- Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte

- The Corsair by Byron

- Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

- Alice Through the Looking-Glass by Lewis Carroll

- Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan

- Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett

- Jean-Paul Sartre’s The Jewish Question

- The Martian Chronicles by Ray Bradbury

- The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens

- David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

- The Prince by Machiavelli

- Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, volumes one and two

- Tales of Mystery and Imagination by Edgar Allan Poe

- The Memoirs of Saint Simon

- The Weir of Germiston by Robert Louis Stevenson

Book-burning in Fahrenheit 451:

On the “making of” feature on the DVD, producer Lewis M. Allen shared this tidbit about censorship he experienced during the making of the film:

An interesting thing about censorship is that when we were doing the book burning scene, the studio… wanted to eliminate all books that were by living authors that were not in public domain, and the fact that they may be sued or whatever. And we just ignored that. We said, the hell with it, because I think everybody, anyone who was around who had a book being burned in there would be very much flattered by it. … So we ignored that and went right ahead.

Allen also shared an amusing anecdote about how they compiled and played with all those books for the book-burning scenes:

To me, the most interesting part of the film… was the burning of the books, which went went on and on. And we had those books in our offices, we had hundreds of books, from the beginning of the film. And he would play with them. We’d go round and pick ones out, play with them, and toss them, and put piles and so on. Every day this was done, as a kind of ritual, which was fun to do, ‘cause we’d come up with strange books.

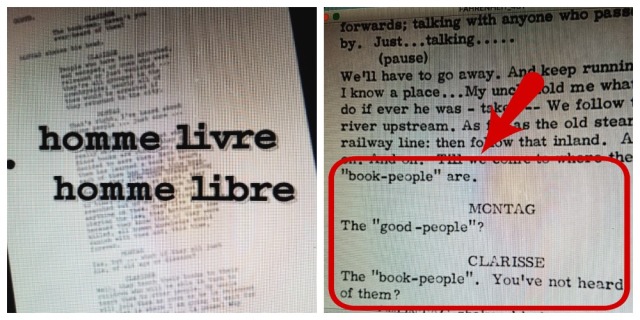

Homme livre/libre:

The screenplay was originally written in French, as it was director François Truffaut’s vision, so there were several puns that got lost when translated into English.

One of the best puns focused on “homme livre” versus “homme libre.”

The original script had a moment between Clarisse and Montag, in which Clarisse explains about the “homme livre,” which translates to “book man.” But in French, “homme livre” sounds very close to “homme libre,” which translates to “free man.”

As producer Lewis M. Allen shared on the “making of” DVD feature:

That was a nice pun, about the book people and the free people, livre and libre, which could not be translated.

Definitely an attempt to preserve the nature of the original pun in French, but it’s a pale ghost of the original.

Homage to the written word

The ultimate message of Truffaut’s film version of Fahrenheit 451 gets discussed by several people in the DVD features.

From film historian and critic Annette Ensdorf:

What you’re going to get is Truffaut’s really passionate homage to literature, to the written word, to the notion of a text as a living, breathing entity and process that can still affect us.

Ensdorf’s thoughts on the ultimate significance of the book people’s actions:

You learn it [the book] by heart, through the process of love. […] Is there not freedom in the very choice of which book you want to be?

From producer Lewis M. Allen, who praised Truffaut playing down several of the more overt sci-fi elements in the book, like the “mechanical hound,” because:

It would be very distracting, in fact, from the simple story of the books, which was really what he was interested in most of all.

From Steven C. smith, biographer of composer Bernard Hermann, who composed the music for the film and who was personal friends with the book’s author Ray Bradbury:

The act of reading becomes… the most romantic thing in Fahrenheit 451.

And in the music feature on the DVD, Ray Bradbury summed up the themes of the film’s musical score and its connection with the story itself:

What we have is a romance with books.

Final words from the author himself:

The DVD that I checked out of this film also included in its special features an interview with Ray Bradbury, who talked about how he first wrote the book in a library basement and how the title came about.

On reflection in 2002 special feature on the DVD by Universal Studios, Bradbury remarked:

I am a library person. I never made it through college you see. I’m self-educated in the library so anything that touches the library touches me.

You can also read a bit more background info and personal quotes from the author in my obituary post for Ray Bradbury, who passed away in 2012 at the age of 91. He was a lifelong and vocal supporter of libraries, and as he stated in 2009:

Libraries raised me.

Here’s to the “book people” around the world who stand up to censorship and advocate for reading, books, libraries, and librarians. ♥

Have you read the book and seen the film version of Fahrenheit 451? Please share your thoughts and leave a comment below.

Sources used:

- Fahrenheit 451. Dir. François Truffaut. Perf. Oskar Werner, Julie Christie, Cyril Cusack. Universal Pictures, 1966.

- The Handmaid’s Tale. Dir. Volker Schlindorff. Perf. Natasha Richardson, Faye Dunaway, Robert Duvall, Aidan Quinn, Elizabeth McGovern. Cinecom, 1990.

- “An Introductory Powerpoint: Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury” by Christine Samantha Anderson via SlidePlayer

- Soylent Green. Dir. Richard Fleischer. Perf. Charlton Heston, Leigh Taylor-Young, Edward G. Robinson, Brock Peters, Joseph Cotten. MGM, 1973.

I recently watched this film again with my nephew who had studied it at college this year. We discussed the film at length afterwards and between his reading and our re-watching of this film, it was so much more interesting. One puzzle I had was what book was Clarisse going to learn? I was surprised that the book she chose wasn’t clear in the movie. I’m assuming it is The Memoirs of Saint Simon? I know Guy Montag chose Poe’s Tales of Mystery and Imagination. Anyone else have get a different read on this? Also, what would be the significance if Truffaut had Clarisse learning Saint-Simon, if any?

I agree, this film is so much more intriguing upon multiple, in-depth viewings. My assumption is also that Clarisse’s book is The Memoirs of Saint Simon; in the end scene, she is reciting French. This is very different from the source novel, of course; Clarisse’s role was much more extended in this film version. (I haven’t yet seen the new HBO version starring Michael B. Jordan, so I don’t know how Clarisse is depicted in that one.) I looked up a few theories online to see what others, if any, had mused about the significance of Clarisse’s choice of book. In a biography of Truffaut by Annette Insdorf, the author hints that the choice of Clarisse’s book being a *memoir* is significant, especially when contrasted with Montag’s wife, Linda, who cannot remember when they first met.

I watched Fahrenheit 451 several years ago and enjoyed it very much. I had never read the book and knew little about it beforehand but the subject piqued my interest and I was not disappointed. As I watched it, I was appalled at the idea of such a thing becoming a reality. Of course, that was Bradbury’s intention. I thought it was brilliant to have “fireman” become fire starters as opposed to firefighters which makes much more sense to me. When I was a kid, the accepted term for emergency crews that put out fires was “fireman” until it gradually evolved into “firefighters” which is much more fitting. I wonder if the book or movie influenced this change? Maybe “fireman” took on a negative connotation after Fahrenheit 451.

It’s a nice idea, but I’m fairly certain it was just part of the trend away from gendered language: over that same period policemen became “police officers” and mailmen became “postal carriers.”

It is an interesting idea! And I agree, it was brilliant of Bradbury to put that twist on “firemen” to be fire starters instead of fire fighters. Part of his lasting legacy to literature ❤