My Irish counterpart, Colin @ Libraries at the Movies, posted some thoughts on Alfred Hitchcock’s 1929 film Blackmail a little over a year ago — and I’m just now getting around to rewatching this early Hitchcock film. Admittedly not his best film, it was a big commercial hit and was the first British sound film as well as the first example of sound dubbing. Blackmail also includes quite a few experimental touches and echoes of what would become Hitchcock trademarks, and the film features the Round Reading Room of the British Museum. The Round Reading Room — which, alas, was relocated in 1997 — was also the model for the Library of Congress Reading Room.

*SPOILER ALERT*

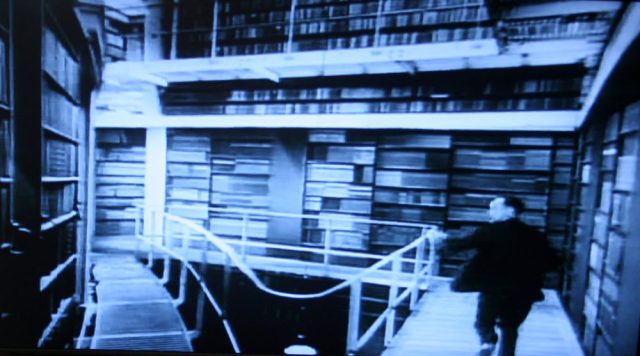

The final chase scene takes place in the British Museum, culminating in the Round Reading Room.

Although no librarian is featured, landing this film in the Class V category, there are several shots of the library. These shots include a birds-eye view overlooking the famous vista, as well as some behind-the-bookcase chase scenes.

The finale is atop the library dome, and Hitchcock gets to show off his amazing visual style, silhouetting the blackmailer and the policemen scurrying across the dome. Finally, in his panic, the blackmailer falls through the dome. The policemen rush up and look over the shattered glass, where one can make out shapes of the round bookshelves far below.

As a librarian, I did gasp out loud and shout at the screen, “No! He’s ruined the library!” Perhaps only a librarian would be so horrified at the thought of a body crashing through a library ceiling. I mean, imagine the gore and mess below with the library resources and furniture!

But that’s the genius of a good director. At his best, Hitchcock created suspense and horror by what he didn’t show.

So why did Hitchcock feature the British Museum and the Round Reading Room? Colin makes a good case that:

“The library is significant because of where it is — the only way out is up, and up is where Hitchcock characters go to fall or jump off things. The director cares nothing for the library qua library.”

I agree, Hitchcock chose the library because of its visual impact — but what an impact! It’s a pretty powerful statement that the British audience watching this film would have felt immediately connected to the Round Reading Room — and even those American audience members who would have recognized the design behind the Library of Congress. It’s also a study in contrasts; the library’s history of tradition and conservatism is emphasized even more by being tainted by the blackmailer and the indignity of a police chase.

Although based on a play of the same title by Charles Bennett — who also penned some of Hitchcock’s best British films, including 1934’s The Man Who Knew Too Much, 1935’s The 39 Steps, and 1936’s Secret Agent — I have not been able to locate a full-text version of the original play to doublecheck the setting of the final act. The play, which apparently was based on real life events, was a commercial flop in 1928 and starred Tallulah Bankhead. If you’re able to locate a copy of the original play, please let me know!

Sources used:

- Blackmail. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Perf. Anny Ondra, John Longden, Cyril Ritchard. British International Pictures, 1929.

- “British Library” via Wikipedia is licensed under a CC BY SA 3.0 license

- Higgins, Colin. “Blackmail (1929).” Libraries at the Movies, 14 March 2012.

You’re right, of course. The finale is no geographical accident. Note how the villain is first pursued through the Egyptian galleries, past both the monstrous antiquities which hint at his own evil, and the mummified bodies which prefigure his death.

But I still maintain that the Round Reading Room is too multilayered a space to convey any symbolism. True, Virginia Woolf’s ‘A room of one’s own’, which sets the Reading Room up as the ultimate Establishment space, was published in the year of the film’s release, but Woolf’s perspective is jaundiced. By then the Reading Room already had a long association with radicalism. Eleanor Marx, following her father’s footsteps, attended daily for years. It was a quotidian escape for Kropotkin, Proudhon and Lenin. Late in life Wilhelm Liebknecht noted how In the 1860s ‘the scum of communist Europe’ could be found there.

So while as a library it presents order and structure, in the Bolshevik-fearing 1920s it retained a revolutionary patina. The scenes within the Reading Room seem cursory – just an excuse to get the protagonists onto the roof. Any extended footage would be overly provocative and distracting, perhaps the reason why the later ‘Night of the Demon’ uses a different reading room for its significant library encounter.

I so enjoyed ‘Night of the Demon’ as well as the library scene in that film. 🙂 I love that you slip in phrases like “quotidian escape” and “Bolshevik-fearing” as naturally as breathing air. And wow, what a genius observation that the villain is pursued through “monstrous antiquities which hint at his own evil, and the mummified bodies which prefigure his death” — you have such a way with language!

I love it when you give us little gems like this. Thanks for a good read.

Wow, thanks! It’s interesting which posts different people respond to — sometimes I’m quite surprised at the reactions! 😀